After more than a year of community meetings, negotiations, resolutions and legal action, the pipeline company Kinder Morgan is getting ready to begin construction on the Permian Highway Pipeline in Central Texas—at least if legal challenges do not stop it.

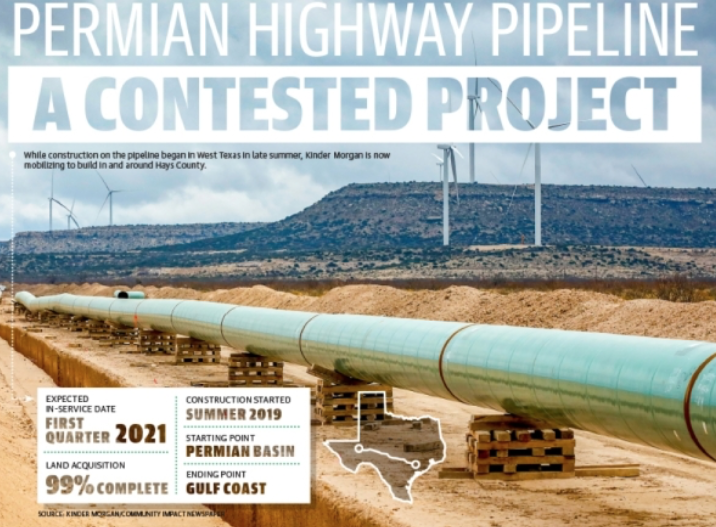

Work has already begun on the westernmost section of the 430-mile, $2 billion natural gas conduit, which stretches from the Permian Basin to the Gulf Coast, nearly bisecting Hays County. But in the Central Texas area, the company is waiting for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to issue required permits.

It is what happens with those permits that will most likely determine how soon Kinder Morgan can break ground.

The endangered species question

The permit issue is at the heart of two letters of intent to sue—required before filing a lawsuit against a federal agency—filed in the last six months to try to force Kinder Morgan to perform a full and public environmental review.

The first letter, filed with the U.S. District Court on July 17, focused on the impacts of the pipeline on the golden-cheeked warbler; the second, filed Oct. 16, focuses on aquifer-based species such as salamanders.

Hays County and the Travis Audubon Society signed onto the July letter, while plaintiffs in the second included Austin, San Marcos and Kyle, in addition to Hays County.

Both letters charge that the Permian Highway Pipeline passes through endangered species habitat and that the company is trying to avoid rigorous environmental review by seeking a general nationwide permit from the Corps, which would not require it.

The members of the Texas Real Estate Advocacy and Defense Coalition funded both letters of intent, and there is a high likelihood that the organization will sue if the project were allowed to move forward with the less limited permit, according to attorney David Braun, legal council for the TREAD Coalition.

“If those permits are issued without the environmental studies that we think should have been required, I think it’s almost a certainty that TREAD will try to file a lawsuit,” Braun said.

If a lawsuit is filed, it will include a request for an injunction, which would at least temporarily keep the company from building if it is granted.

The lawsuit, however, could go forward even if the injunction is not granted—and it may not be. The legal standard for granting an injunction, Braun said, is that a judge must decide both that the plaintiff will likely succeed in court and that not granting the injunction would incur irreparable harm.

“We feel good on both those points,” Braun said. But he added, “The injunction is a very high hurdle.”

Read more from Katharine Jose with Community Impact Newspaper here.