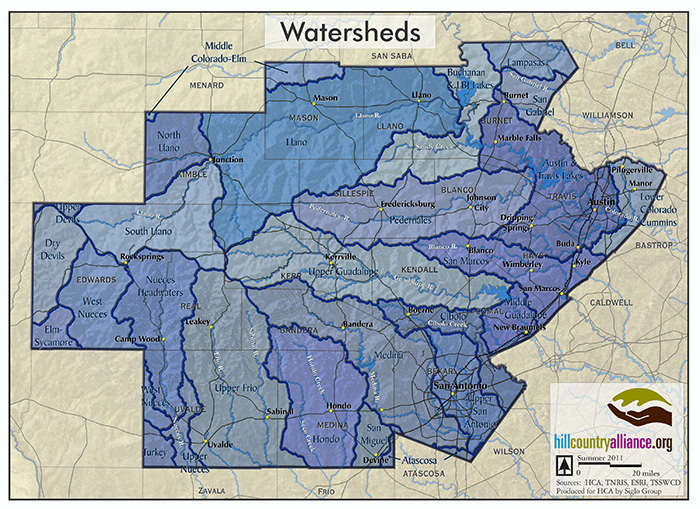

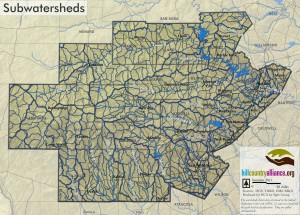

Water Catchment Areas (Watersheds)

Water Catchment Scale Planning and Conservation

Water catchments are widely recognized as the most effective management unit for the protection of water resources, both water quality and supply. A water catchment (commonly referred to as a “watershed”) is an area of land where all water flows to a single stream, river, lake or even ocean. Natural boundaries of water catchments can be very small for a single creek or stream or quite large—the Colorado River basin for example. HCA encourages the use of the term “water catchment” over “watershed.” A water catchment area is home to a complete water-cycle system. In order to manage these systems for a healthy future, we must learn to catch, conserve and make wise use of all water in the system, rather than “shed” that water away as the term “watershed” implies.

The concept of “Water Catchment” is common around the globe

“A catchment is an area where water is collected by the natural landscape. In a catchment, all rain and run-off water eventually flows to a creek, river, lake or ocean, or into the groundwater system. Natural and human systems such as rivers, bushland, farms, dams, homes, plants, animals and people can co-exist in a catchment.” – Sydney Catchment Authority

Healthy catchments provide:

- A source of clean drinking water

- Unspoiled natural areas for recreation

- Habitat for plants and animals

- Healthy vegetation and waterways

- Reliable and clean water for stock and irrigation

- Opportunities for sustainable agriculture and industry.

Our daily activities affect the health of our catchments. The first step to protect our catchments is to better understand our impact on them.

Water Catchment Protection Planning in Texas

Water catchment protection planning in Texas typically addresses water quality issues for creeks and river systems that are threatened or “impaired”. While water catchment planning can take many forms, it is common for funds to come from EPA through the Clean Waters Program in the form of “319 Grants”. These are locally developed, holistic plans that coordinate activities and resources to manage water quality. The TCEQ has helpful resources on this type of planning process here.

Here in the Hill Country, we have identified eleven water catchment protection plans in the works. Click here to view a helpful map of our region and a legend to the water catchment protection plans we currently know of. What’s encouraging is that we are beginning to see movement to a more proactive approach to planning. Stakeholders along the South Llano for example include the South Llano Watershed Alliance and TPWD working together for Guadalupe Bass restoration and overall watershed stewardship goals. The Cypress Creek Watershed Protection Plan is addressing stormwater runoff in a developing watershed. And in Boerne, the City has partnered with area stakeholders to develop a proactive, non-regulatory program to address impacts of suburban growth and development.

Water Catchment Scale Land Conservation – Conserving Land Conserves Water

Water and land are inseparable; clearly what we do on the land affects water resources within a water catchment. There is tremendous public value in adopting policies that reward landowners for practicing stewardship that enhances our region’s water supply. In general, HCA supports these types of policies and hopes to help identify new and creative ways to develop “market-based” solutions to land/water conservation.

Legislation passed in 2011 would have allowed for a new land valuation (tax benefit) for water stewardship practices on private lands. This program was promoted by the Nature Conservancy of Texas as a new national model for rewarding landowners for protecting and enhancing water resources that ultimately benefit the public. In order to go into effect, the public needed to pass “Proposition 8” in the fall of 2011, which did not happen.

Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) programs have been promoted for many years yet rarely funded. The idea is to create a fund to help pay for conservation easements that will ultimately limit development on private land (voluntarily) in exchange for tax benefits.

Hill Country River Basin Literature

All of the rivers between the Rio Grande and the Upper Colorado are born in the Hill Country and provide life-giving sustenance for municipalities, livestock, and wildlife from their headwaters to the Gulf Coast. Indeed, much of the Texas industrial, tourism, electric generation, and petro-chemical complex depend on reliable and clean water from these rivers.

A growing body of research has been produced in order to better understand and protect the critical aquifer and river resources that maintain our health and economy. Among them are studies of general basin characterizations, spring-flow/base flow regimes, hydro-geologic interchanges, and others.

Below is a set of current studies with links to the full report as published.

Frio River — Biology and Fluvial Geomorphology Study to Determine Impacts of Sand and Gravel Activity

The summer vacation favorite upper Frio River contains only 0.013% of the total stream mileage in the state. But between 2007 and 2016, 11% of the entire state’s aggregate mining permits were for excavation on the Frio’s beautiful banks. This 2019 Texas Parks and Wildlife report documents the flora and fauna in and along the Frio River, and the impacts that aggregate mining operations are having on that once pristine river.

Pedernales River — The State of the Pedernales: Threats, Opportunities and Research Needs

The Pedernales River is an iconic Hill Country river, running 106 miles through rolling limestone hills before eventually joining the Colorado River at Lake Travis. The Pedernales drains nearly 820,000 acres across 8 counties. During dry periods, the Pedernales River provides up to 23% of the surface water entering Lake Travis, which the city of Austin relies on for drinking water, energy production, and recreation. The Pedernales and its associated watershed area provide critical habitat for several endemic species, and the river provides important scenic, recreational, and cultural value to Central Texas. Read HCA’s 2015 The State of the Pedernales summation of the research, conservation, and stewardship efforts that have been completed or are currently active in the Pedernales River watershed.

Pedernales River — How Much Water is in the Pedernales Watershed?

This ongoing suite of research by the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment includes on the ground information on surface flow measurements, baseflow volumes from aquifers, land cover impacts on water quality, gain/loss measurements, and a Watershed Atlas.

Upper Guadalupe River — The Upper Guadalupe River: Stewarding a Hill Country Icon

The Upper Guadalupe River is one of the iconic rivers of the Texas Hill Country, originating from an aquifer under the western Edwards Plateau, and cutting canyons for 187 miles through rolling limestone hills. Before eventually reaching the confines of Canyon Dam in central Comal County the Upper Guadalupe drains nearly 1,427 square miles and touches seven counties. The river provides water for recreation, agriculture, fish, game, and humans. Commissioned by the Guadalupe River Association and written by HCA in 2017, The Upper Guadalupe River summarizes research and stewardship efforts in the Upper Guadalupe River basin. Understanding the river’s unique characteristics, the diverse land uses that take place within the basin, and the wide variety of stakeholders interested in its long-term sustainability will inform future efforts to protect its economic and ecologic vitality.

North Fork Guadalupe River, from the Upstream Boundary of the Kerr Wildlife Management Area to the Farm-to-Market 1340 Bridge Crossing at Mo-Ranch

A 6.4 km reach of the North Fork Guadalupe River between the upstream boundary of the Kerr Wildlife Management Area and the low water dam downstream of the Farm-to-Market 1340 bridge crossing at Mo-Ranch was surveyed to assess instream physical habitat, water quality, fish, mussel, and macroinvertebrate assemblages, riparian area, and public access locations in April 2012. This Texas Parks and Wildlife report documents the exceptional aquatic wildlife along this beautiful stretch.

Llano River — The Headwaters of the Llano River

The North and South Llano Rivers are a valuable resource to Central Texas, providing recreational opportunities, habitat for unique plant and animal communities, and water supplies to local and downstream communities. The protection and preservation of the flow of these rivers and their watersheds has been identified as an environmental, economic, and cultural concern. The 2012 Headwaters of the Llano River is a characterization and comparison of the rivers, springs, and watersheds of the North and South Llano Rivers and was prepared for the South Llano Watershed Alliance in conjunction with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department by Tyson Broad.

South Llano River — Land of the Living Waters

The South Llano River has not ceased flowing in recorded history due to the presence of several large springs. The largest of these springs is Big Paint Spring, followed by the more famous Seven Hundred Springs. These two springs, along with numerous other springs and seeps along the South Llano River, annually provide about 80% of the flow downstream to the Llano River. During dry periods, the Llano River provides about 75% of the flows to the Highland Lakes, the major water supply for the City of Austin and other downstream water users along the Colorado River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. The 2008 Land of the Living Waters report prepared for the Environmental Defense Fund and written by Tyson Broad attempts to facilitate potential stakeholder efforts by providing a characterization of the South Llano River, its springs, and its watershed, as well as suggesting recommendations to address identified water management issues.

James River — The Unknown River of Central Texas

The James River is little know in the Hill Country, but it is ecologically unspoiled and economically significant tributary of the Llano River. The spring-fed flows of the James River and its tributaries provide exceptional habitat for unique biological communities, and provide water supplies to domestic, livestock, and wildlife in a region with limited surface waters. The 2010 Unknown River of Central Texas written by Tyson Broad for the Environmental Defense Fund characterizes the river and describes its significance to the Hill Country.

The Nueces River – 2013 Basin Summary Report

The Nueces River Authority’s 2013 Basin Summary Report covers all of that agency’s territory including the San Antonio-Nueces Coastal basin, the Nueces-Rio Grande Coastal basin; and the basins, bays, and estuaries of the Nueces River, including the Aransas, Mission, Atascosa, Frio, Leona, Sabinal Rivers — and their associated creek systems. This document is primarily a snapshot of water quality however, there are good data to be found including targeted outreach, maps, and riparian resources.

The San Marcos River — An Evaluation of Spring Flows to Support the Upper San Marcos River Spring Ecosystem

Waters issuing from the Edwards Aquifer through San Marcos Springs at the headwaters of the San Marcos River constitute the second largest spring system in Texas and the most historically consistent spring system in the southwestern United States. This study details how historically stable flows from the springs have fostered a wealth of endemic species, human settlements, and a thriving economy.

Recent Water Catchment News

Hill Country rivers at risk of historic lows ahead of tubing season

"In general, the Edwards Aquifer and San Marcos springflow levels are currently at levels that have only been experienced less than 10% of the time in recorded monitoring history and approaching the lowest levels on record for this time of year," Enders said in an...

Texas utilities are storing their water underground. Here’s why.

Among the most striking signs of Central Texas' ongoing drought are two of the region’s reservoirs: Canyon Lake in Comal County and Medina Lake, west of San Antonio. In both lakes, the water levels are historically low. For the first time since it was filled in the...

Texas lawmaker files bill to reduce “forever chemicals” in sewage-based fertilizer

Johnson County’s newest state representative, Helen Kerwin, R-Cleburne, filed her first bill Friday targeting an environmental problem that has struck her county: PFAS contamination in sewage sludge-based fertilizers. Kerwin said House Bill 1674, could reduce the...

Austin has little to no ‘forever chemicals’ in its drinking water. What did the city do right?

New testing results show Austin has little to no traces of forever chemicals in its drinking water. Exposure to these chemicals, also known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS, have been linked to prostate and kidney cancers, thyroid conditions, decreased...